Vanilla & One Shorter Story

two flash fictions and some film subtitles.

Hello.

Lately, I have been feeling the itch to publish something here—some essay, some article, some rambling, some story. This letter is an exercise in scratching that itch.

It’s never been my intention to use this space to share my creative work (by this, I mean fiction). I prefer to keep my thoughts about the world separate from my hallucinations about it.

I initially descended into a ramble about my rationale for preferring to keep both forms separate, but I have decided to trim all that shalaye.

The first story, Vanilla, is my second most rejected story. I suppose it is a testament to my love for it that I have not dismantled it after all these years.

I wrote the second story on a whim a few years ago after learning that one of my friends was turning twenty or something close. I only remember that I laughed quite a bit while writing it.

Vanilla

1.

One percent mortality, you think as you count the squares that pattern the ceiling, doesn’t mean anything if you’re part of the one percent. Sometimes you forget there was a time before this. Before the great beyond shifted from being the subject of your teenage poems to your reality, any day from now.

You think about how odd it is that Grace, the new nurse at your bedside, is your old classmate. The girl you used to date but broke up with because your mood was darker than your black metal band T-shirts and all you wrote about was death and how you longed for it. It convinces you there is a god making a show of this. It convinces you your death is inevitable. Grace is simply here to bear witness in that sardonic way the universe resolves itself.

2.

Somewhere between sixteen and now, you picked up the zest for life, and for two years you tried denying it, because accepting that you were over Avenged Sevenfold and Slipknot would have made you cliché—in that grotesque way you always believed you weren’t. The average teenage kid dealing with angst by clamping headphones to their head and headbanging to Korn and Black Sabbath. Typical. Vanilla. And it was even more grotesque because you weren’t American or British. You were African, Nigerian, and the majority of your peers, they dealt with their angst in different ways.

Grace called you a wannabe goth kid the day you broke up. You wondered how long she had kept that in. This thing, she said, it won’t last. Your sadness, it’s not even real. You want to be depressed and look goth so bad for the aesthetics. It’s performative. You wear black clothes and cling to weird music bands to seem weird, different, ostracised, because without them, there is nothing different about you. You are vanilla. You do not stand out.

You cried that night. Her words cut into your heart like a motherfucker.

Anyway, your sadness, it was real, and at that time, you wanted to tie boulders to your feet and walk into the Atlantic. That was too far, so you romanticised drowning in the local river, or the Niger where no one would find your body. You refused to learn how to swim.

In those years, headbanging to those bands was your way of coping. And when you started to outgrow them, because you had made them so integral to your identity, you panicked. Like a middle-aged man clinging to his skinny jeans. You couldn’t accept that you no longer needed them, were no longer that teenage kid. And you thought maybe Grace was onto something when she called you vanilla.

3.

So, Grace. You last saw each other five years ago. She was in her third year at the University of Ibadan. You were at Ife, in your second year because you had dropped out of your English major—after losing the darkness that drove all your poetry in your first year—to pursue something more practical. Like law.

You were convinced your sadness would last forever, and it broke your heart to pieces when it didn’t.

Grace sits by your bed now and asks you how you are, how you’ve been. You trade calcified pleasantries and size up each other in your minds; you both juxtapose what you see now with what your potentials seemed like back then. She is all she seemed she would be.

You always told her you wouldn’t live to be twenty-one. If the noose didn’t do it, the water would. You wonder if she remembers this. Twenty-one is long behind you now.

She mutters a prayer for you to recover quickly. She’s always been religious like this. Even though you say amen many times in your mind, you look at her and shrug nonchalantly as you used to every time she said she didn’t want you to off yourself someday, like you considered life too trivial to want to extend.

Do you, she asks as she gets up from your bedside, still listen to those weird bands of yours?

You hesitate, stare at her for five seconds while you contemplate what to say. And then you give her a deliberately ambiguous shrug.

You Started to Realise You Were a Teenager a Little Too Late

1.

You started to realise you were a teenager a little too late, at nineteen, when you were already forgetting what it was like to be a teenager. So you ran to your local bookstore and bought a journal.

Every day, you spent a few minutes digging deep into your earliest memories of being a teenager, recording, trying to remember what being a teenager felt like, had felt like. It pained you to admit, even to yourself, but you were no longer cool to the cool kids. The sixteen-year-olds on your block now regarded you as one of the adults. You felt awkward every time you tried to blend in with them.

2.

The truth is you were never a cool kid. On some days, you couldn’t tell if your difficulty dredging up memories that felt authentically sixteen was because time is the devil that eats all memories or because there were no memories to dig up.

When your cool friends who also were no longer sixteen talked about the things they did at sixteen, you always felt a sense of loss, of wasted time, wasted youth. You could never relate. All the fun and buzz.

It always felt like you hadn’t really lived.

3.

After a month of journaling, a few days before you turned twenty, you broke down in a corner of your local nightclub—a marijuana roll between your lips as you attempted to create something to remember—and you cried the fuck out of your eyes. For some strange reason, you felt the urge to press your wet cheeks against the warm, dusty floor.

You had spent a month trying to crystallise your memories of what it felt like to be authentically a teen in your journal and failed. What will you refer to when you try to deal with your teenage children? When you try to befriend them? When you try not to be the parent who doesn’t understand?

And so you cried. And cried some more.

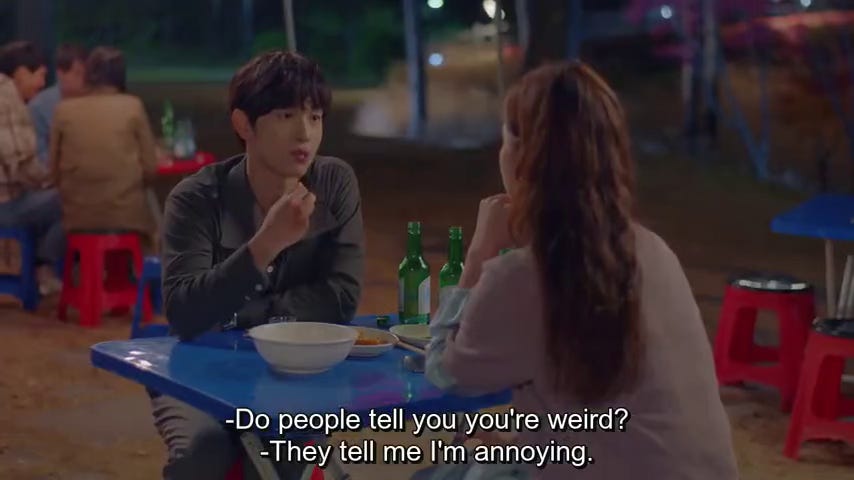

I am unsure how to close this letter, so here are some film subtitles I took last year. They’re from the Korean drama Run On.

For some reason, I have been replaying ayra’s commas & bad vibes nonstop since morning. commas, especially.

Share if you liked anything here.

Until next time.